FST JOURNAL

Edge Technologies

DOI: https://www.doi.org/10.53289/BARY7006

What is needed for an ethical future with Edge Technologies?

Dr Peter Novitzky

Dr Peter Novitzky is a senior research fellow at PETRAS National Centre of Excellence for IoT Systems Cybersecurity. He is also a research fellow at the Faculty of Engineering, Department of Science, Technology, Engineering and Public Policy (STEaPP) at University College London and an Associate Professor of Ethics of Emerging Technologies at Avans University of Applied Sciences in the Netherlands. Peter specialises in the ethical challenges of emerging technologies, AI, safety and security.

Summary:

- The ethics of AI technologies for assisted living is a convoluted and complex area due to the sheer number of topics and complexity of different points of view

- The art of an ethicist is to pick the most relevant aspects and highlight them, justifying the course of action

- The small number of visionaries deciding what big tech comes next means that there's a high probability of something going wrong either in terms of financing or agenda setting

- Ethical work on the distant horizon is intellectually appealing, but arguably a diversion from the harder problems of the present

- We need more specialists in the socio-technical fields who can engage and work across the spectrum.

The role of an ethicist

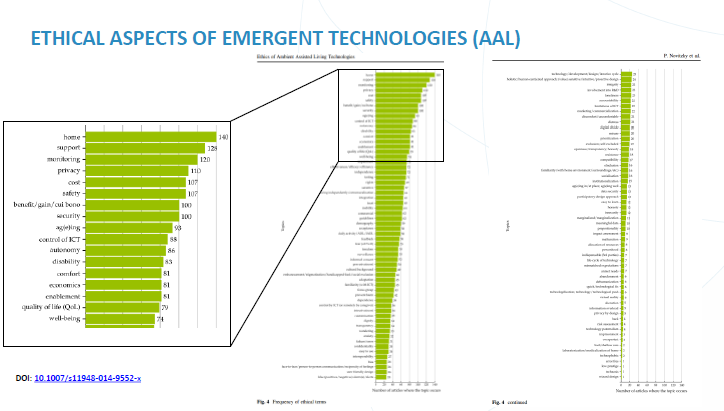

Recently, with the help of other experts, I worked on a definitive list of all the ethical issues related to ‘ambient assisted living’ technologies. These are AI technologies supporting people with mild cognitive impairment such as dementia, to age and stay longer in their home environment. It was a review of more than 300 papers.

The other paper that I was fortunate to co-author was on the role and impact of emergent technologies on intimate partner violence (IPV). What both investigations highlighted is how convoluted and complex these areas are. From a general, ethical perspective, this is due to the sheer number of topics, and complexity of various stakeholder’s point of views. What both of these papers emphasise is that modern technologies have a tremendous amount of ethical challenges.

Moreover, there are some very complex entanglements between, e.g. the public, private or communal individual approaches; the relationships between stakeholders who are associated with these technologies affected directly or indirectly. An example for the latter are people living with dementia, their informal and formal carers, healthcare professionals. We are also dealing as a species with wider, societal challenges (or so-called wicked problems) that by definition cannot be easily solved, even with the help of the newest technology. However, we still try and the role of an ethicist in this is to pick the most relevant challenges that need attention, so we ensure respect, rights, and universal and societal values.

The standard definition of ethics is a systematic reflection on questions of morality (rules, guidelines, principles), values, judgements, normative decisions, and the justification of these. It is an intellectual inquiry about the concepts and principles that help assessing behaviours that help or harm sentient creatures, by providing arguments for choosing one or another course of actions.

Cybersecurity

As a representative of the PETRAS National Centre of Excellence for IoT Systems Cybersecurity, it's always intriguing to focus specifically on the cybersecurity area of emerging technologies. A report of an influential group of researchers written in 2018 entitled “The malicious use of Artificial Intelligence: Forecasting, prevention and mitigation”, although aged by current standards, collates all the digital, physical and political connotations of AI cybersecurity. The reason why I use this report is to put these cybersecurity AI threats into a chronological context. Most of these malicious AI uses have already taken place since the publication of this report, or—with the exception of one—are currently happening. This list of threats highlight the challenges ahead of us: what AI-related cybersecurity issues we might face, and how ready we are in terms of tackling them. To further qualify this debate, the Digitalization Index, based on 23 indicators throughout six key attributes (like ubiquity, affordability, reliability, speed, usability and skill) categorise countries between four areas: constrained, emerging, transitional and advanced countries. Most of the countries on the Western hemisphere belong to the digitally advanced countries, which also means that our potential cybersecurity vulnerability-exposure is globally the highest.

The graph above demonstrate that, for example, Russia is represented on the Digitalization Index as an advanced country; China is still a transitional one. Again, I believe this graph demonstrates well how vulnerable our societies are and will become in terms of cybersecurity in the future.

My library

In the second half of my speech I would like to invite you to my library. I recently read Daron Acemoglu’s book ‘Power and Progress’ (2023). As an MIT (Massachusetts Institute of Technology) professor of economics, together with Simon Johnson, they looked at the last 1000 year struggle over technology and prosperity, trying to answer how much innovation and regulation we need. They explore a problem that we currently see across the high-tech and AI-debate, which is that a handful of visionaries set the agenda for the next big technology and where the funds will be invested. Such a small number of people sitting at the top means that there is a high probability of something going wrong either in terms of financing or agenda-setting. Acemoglu and Johnson raise the point that we should strengthen our democratic institutions and decision making processes, involving citizens into these to a greater degree. If there is one argument which summarises their book, it is that throughout history, the ‘trickle down’ prosperity or economy never worked. This is the challenge that we are facing in terms of technology today too.

The other book that I would highly recommend is Sir Prof Geoff Mulgan's book ‘When Science Meets Power’ (2023), also published very recently. He very poignantly formulates a critique of us, fellow philosophers like myself and my colleagues, by writing that many non-philosophers started to consider the work on AI-ethics as a distraction rather than a solution. Many books and conferences investigated high-level moral dilemmas of the trolley problem, others explored the challenges of ‘singularity’ with the hypothetical Artificial General Intelligence. Yet, at the same time AI has been applied in almost every area of our daily lives with very little in-depth and practical analysis on the social and ethical issues. While these analyses of the distant horizon was certainly intellectually important, Mulgan argues that these were “a diversion from the harder problems of the present” (p. 78).

I fully agree with this statement. I would like to focus on more applied challenges such as dementia and intimate partner violence and how that actually translates in practice. We see a huge influx of ethical frameworks, tools, and methods over the years. Yet, it remains to be seen which of these scale-up to a domain-wide level, or which and how frequently they are validated by other researchers? Other questions also remain to be answered: do we have enough staff to test them all? Who applies them? Where on a national or global landscape these frameworks scale up?

This brings me to the conclusion of my speech: we need more specialists in the socio-technical fields, who can engage and work with citizens, users, researchers, industry partners, and the developers of these technologies.