FST JOURNAL

Quantum Technologies

Quantum technologies have a potential role in both national security and civil society, as well as commercial opportunities. The UK has huge research strengths in quantum technologies and a burgeoning quantum start-up ecosystem. Whilst some potential uses of quantum technologies are still a way from commercialisation, others are right here. On Tuesday 24th September 2024, we explored where the UK currently sits in quantum technology and what is needed to transition from research into real-world applications - both in the public and private sectors.

DOI: https://www.doi.org/10.53289/RFUG8310

Collaboration is Key to Embrace the Quantum Challenge

Professor Melissa Mather

Professor Melissa Mather obtained a Bachelor of Applied Science, majoring in physics, and a PhD in the Centre for Medical, Health and Environmental Physics at the Queensland University of Technology, Australia. Melissa then undertook research positions within the Faculty of Engineering, University of Nottingham, the National Physical Laboratory, and Keele University, UK. She is currently a full professor in the Faculty of Engineering, University of Nottingham, where she holds the Royal Academy of Engineering Chair in Emerging Technologies. This is a 10-year programme of work focused on developing integrated diamond photonic platforms for the next generation of quantum sensors.

Summary:

- International partnerships and collaboration are crucial to unlocking the full potential of quantum technologies.

- The UK is at the forefront of quantum sensing research.

- Although the quantum landscape is brimming with potential, it cannot exist in isolation.

- To realise the transformative impact, we need to embrace adjacent technologies such as precision manufacturing.

- There are many transferable skills that we could consider to efficiently develop the workforce in the short term.

I want to give an academic's viewpoint on where we are with quantum, particularly focusing on quantum sensing, since that is an area I am currently working in. Taking Quantum Technologies from research to reality is a challenge for many communities to investigate, and with that in mind, I wanted to take you back in time and consider who has been involved.

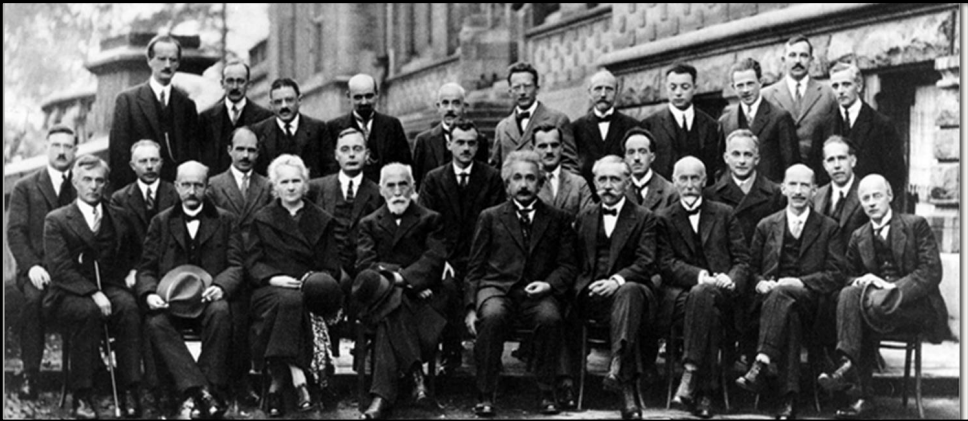

This is a picture from the fifth Solvay Conference, a renowned physics conference series. If we think about 1927 when this was taken, there was real progress in quantum physics and theory. There is a quote from Heisenberg from this meeting which says that this conference had contributed extraordinarily to clarifying the physical foundations of quantum theory. It formed, so to speak, the outward completion of quantum theory. I think that the fact that today, in 2024, we are still talking about Quantum Technologies and quantum physics suggests that we are still very much on a journey. I think that journey is really taking what these pioneering minds had thought and delivering it from research to reality.

Back in 1981, in Boston, there was the first conference noted to have combined physics and computer science. To us now, it may seem unusual that physics and computer science were very separate disciplines, but this was truly a pivotal moment where physicists and computer scientists joined together. And it was at this time when Richard Feynman said, 'Nature isn't classical, and if you want to simulate it, you'd better make it quantum mechanical'. The seeds were planted all the way back here, and the next step was to nurture interdisciplinary ways of working, even at this early point.

Most recently at the Quantum World Congress in Washington we saw collaboration and international partnerships at the centre of conversation and an important piece of the puzzle to achieving the full potential of Quantum Technologies.

If we reflect on this journey in time, we have gone from the world's best minds in physics and chemistry and are now moving towards being in a position where we are talking about international policy and trade. The Quantum ecosystem is blooming from the early seeds planted.

The UK as a Quantum Stronghold

In the UK, we are fortunate to have tremendous strengths in quantum sensing, both in the research domain and in development. I think we can safely say that the UK is at the forefront of quantum sensing research. A good example comes from the University of Glasgow, where there has been a major breakthrough in quantum gravimetry. They are harnessing these compact, portable devices which are going to have applications in civil engineering, environmental engineering, and many more. This exemplifies world-class applications and the commitment to addressing real-world challenges.

To be honest, Scotland could be a quantum country in its own right. For example, there is a Single-Photon Avalanche Diode (SPAD) camera being developed jointly by the University of Glasgow and Heriot-Watt University. So, you have a camera that captures light at extremely low light conditions. You can see the unseen by seeing obscured objects, and this has the potential to transform things such as vehicle navigation and even assist people in locating things in disaster zones.

Further south, the University of Birmingham has been working in the area of gravimetry and has spun out a company called Delta G. They have been using atom interferometry to enable tiny changes in gravity to be measured that will have a real impact on looking at hidden infrastructure in civil engineering applications, considering potentially groundwater levels, and indeed in general exploration underground. Ten years ago, we could not have anticipated this to be a reality, but we are now in a position where we have these types of quantum sensors out and about.

Another example is the National Physical Laboratory (NPL),, which is looking at a sort of Radiofrequency (RF) electric field probe. NPL has a whole set of resources dedicated to Quantum Technologies, and as well as having quantum devices, the UK is in a great position to be able to offer calibration services and set standards for quality products. I do not think you can look much further than NPL, with its long history in this area.

Closer to where I am, at the University of Nottingham, there are optically pumped magnetometers that can map the very weak magnetic fields in the brain. This overcomes the use of cryogenic-based Superconducting Quantum Interference Device (SQUID) magnetometers and enables people to move while they are being scanned. This will have benefits, particularly for younger people, who would find the confinement of SQUID-based systems quite challenging.

There is another example from Imperial College London and its spin-out company, Digi stain. They have applied the approach of undetected photons, employing quantum entanglement to observe how they can detect the interaction of light with tissue samples. This system can provide objective measures, helping to stratify types of cancer treatment for people. In this case, they have been focusing on breast cancer.

Quantum Cannot Exist in Isolation

These examples showcase some of the significant outputs that have already emerged, but I think we need to accelerate things further. Although the quantum landscape is brimming with potential, it cannot exist in isolation. To realise this transformative impact, we need to embrace adjacent technologies. I think we need to look at areas such as precision manufacturing. Quantum devices have intricate architectures and nanoscale components, so we need to consider the demand and capability for manufacturing at this level. The packaging of electronics and the heterogeneous integration of components is going to be key. I also often think that with many of the quantum technologies, at some point we are trying to interchange between a photon and an electron, or the other way around, so having the capabilities and skills for that will be quite important.

We also need to build a quantum-ready workforce. We need a holistic approach, and we are fortunate that there are young people who are interested in becoming scientists and engineers and working in technology. The university curriculum is expanding to incorporate quantum technologies beyond just a physics degree, for example, and we have Centres for Doctoral Training (CDTs), which are producing PhD-ready people. However, I think we need a more holistic approach, considering that there are already people in the workforce who possess the capabilities we need. I think there are many transferable skills that we could consider to efficiently develop the workforce in the short term. We are at a precipice with quantum technologies and how they will impact the next generation of technologies, so we need to seek collaboration and work together to embrace the quantum challenge.