FST BLOG

Systems thinking: the key to getting net zero right.

- 9 July 2021

- Technology

- Keyne Walker, The Royal Academy of Engineering

Reaching net zero is an unprecedented objective. It requires transformation across systems of infrastructure, regulation, finance and human behaviour and it will affect every aspect of our lives. This transformation must also occur at a pace never before imagined and be maintained over a timescale far longer than the current policy horizons of governments.

Net zero by 2050 requires rapid and simultaneous transformations of multiple vital, interconnected infrastructure systems.

The changes required across our infrastructure ‘system-of-systems' could be a risky business and requires careful management. There are many ways in which our transport is dependent on our energy system, which is dependent on telecommunications, which is dependent on our built environment and so on. If a country tries to decarbonise each sector separately, without accounting for the connections and mutual dependence across systems, issues or failures can and will cascade and have far reaching knock-on impacts. When infrastructure fails in such a way, those consequences can be costly for people, purses and reputations, as was shown by the Royal Academy of Engineering’s 2012 report Living Without Electricity, a case study of the 2015 blackout in Lancaster and the cascading impacts.

Systems approaches are the related ways of navigating and managing this complexity which have been developed by different disciplines in the last half-century. For net zero, this means developing a framework to align government policy strategically and adaptively to reach net zero, accounting for all the complex technological, social and economic factors which must be balanced. The right systems approach for any one problem draws together an appropriate diversity of stakeholders to:

- develop an understanding of the system and its interacting elements

- identify and develop a shared understanding of the risks and opportunities that need to be managed, and;

- apply creative design-thinking to defining desirable outcomes and how they can be achieved.

Engineering can contribute much in this space. For example, systems engineering is a disciplined approach to managing complicated systems. It is why a jumbo jet with hundreds of components each relying on each other to work with a high degree of reliability can be designed and built in different places around the world and come together in assembly to constitute an assuredly safe, comfortable flying machine. Many other examples of large scale socio-technical, engineered systems are available.

Without a systems approach to policymaking, dealing with climate change becomes like “whack-a-mole”. Reduce emissions in one place, and they might pop up elsewhere – perhaps in a different form or in a different country as our economy is more global than ever. We need to build into the system the evidence, oversight and governance needed to provide all stakeholders the assurance that our actions and interventions actually help to reduce our emissions when a broader view is taken, and whether it is compatible with a sustainable, resilient, efficient and accessible new system of infrastructure.

It is crucial that these changes are co-ordinated to ensure that the future UK infrastructure and technology works together in an integrated, cost-efficient way with zero-emissions and best outcomes for the population.

Getting net zero right

A lot of time and energy has been put into the question of how to reach net zero, and rightly so. But a bigger accomplishment is building a nation that not only reaches net zero, but also has reliable, accessible and joined-up infrastructure to support the behaviour changes needed while providing energy, transport, shelter, leisure, jobs and biodiversity. There are many possible scenarios in which net zero could be technically achieved, but the social outcomes are poor or unacceptable.

There are several ways which net zero could be accomplished sub-optimally. This may be because high-carbon activities have simply been offshored, leading to loss of manufacturing, economic activity and jobs, with no carbon savings. It might be because rising energy demand and poorly allocated costs drove fuel poverty to new extremes. Or because incentives focused solely on reducing greenhouse gas emissions, resulting in further biodiversity loss, pollution issues and critical rare metal scarcity. These are extreme examples, but without careful system management, the net zero transition may fail to provide the wider social and environmental outcomes such as jobs, security, happiness and justice that it could, both to the UK and internationally.

Without a transition plan finite resources such as zero-carbon electricity supply and rare metals are being ‘double-counted’ and relied upon by multiple sectors, and realities are not faced about the effects of so much change at once.

Alternatively, net zero could be reached in a way which offers significant co-benefit across the wider economy, the environment, and ways of life. The transition offers the opportunity to design-in solutions to a range of other problems. There is rightly growing attention and work on ensuring a ‘just transition’, which requires comprehensive planning to avoid the unintended consequences which can result from fast technological change.

While we tend to focus on whether we can reach net zero and by when, it is important also to ensure we are being deliberate about what kind of net zero we have. Balancing the values, visions and technical constraints for net zero is a daunting task, for which the only answer is carefully considered systems approaches. Systems thinkers have developed ways of trying to capture and navigate this complexity at various scales in order to engage many stakeholders at once – and for net zero the stakeholders are all of us.

What can a systems approach to policymaking do for government?

Systems approaches are fundamentally about maintaining the big picture, the context in which your interventions are taking place. This provides policymakers with the ability to better:

- Identify risks and mitigation strategies to reduce the impact of unintended consequences.

- Reveal important synergies and interdependencies between different decarbonisation strategies and different policy priorities, help balance trade-offs and realise opportunities for additional benefits such as improved health outcomes.

- Help account for social, cultural and behavioural factors that can act as both barriers to and levers for change.

- Understand time pressures and sequencing, determining when there is a window of opportunity to intervene and what information is required to inform those decisions.

- Identify elements or pressures in the system which are working against the overall goal, along with points of greatest leverage where interventions will make most difference.

- Monitor effects of policy interventions and adapt responses over time.

- Develop adaptive approaches to manage future uncertainty and target real-time assessment and monitoring.

Source: Prime Minister’s Council for Science and Technology, ‘Achieving net zero through a whole system approach’

What a systems approach to net zero looks like in practice

The net zero transition will be an unprecedented deliberate shift to a new economy, with new infrastructure and new ways of living in them. But fortunately, there is a rich body of research and practical experience to draw from across different levels of decision-making.

Implementing and fine-tuning the governance of net zero is a challenge in itself. It must build a shared vision, connecting disparate decision-making and decision-makers, be supported by robust and well-understood data, retain a democratic mandate, and evaluate objectively what works and does not. Long-term, committed leadership will be crucial.

Systems governance does not necessarily mean more top-down control however; in fact it is necessary for systems approaches to be applied to net zero at every level to join up global, national and local agendas and needs. In contrast, the speed of decision-making required and the importance of local geographies means that local governments will play a key role in local transitions, and to do so will require more capacity, expertise and new forms of direct engagement with the public.

Some aspects of transition are national, such as long-range transport networks, and some are local such as town planning and nature-based solutions. Many also are global, and require close international co-operation. Net zero must have some shared vision across all these levels.

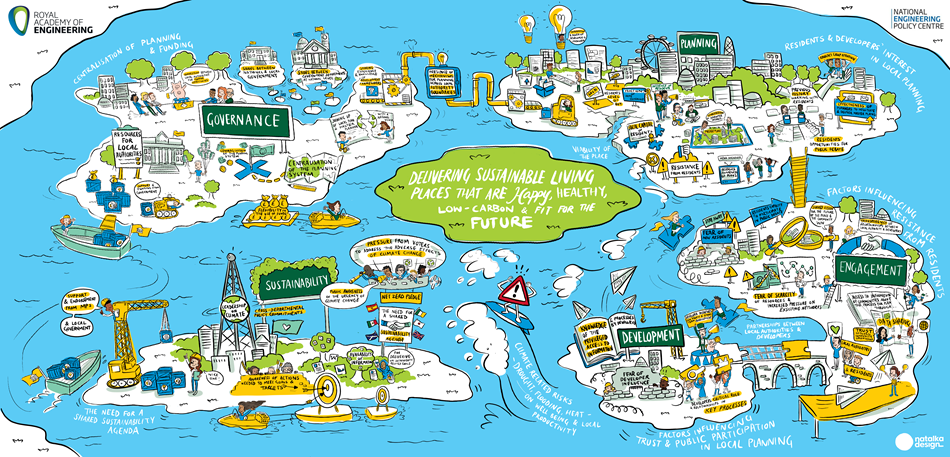

Image source: ‘Our vision of the built environment’

Various models have been suggested for net zero governance, such as in the CST report ‘Achieving net zero through a whole system approach’, from the work of iGov at the University of Exeter, and in ‘Our vision of the built environment’. There is yet more learning to be captured from the practical experience of system thinkers using these approaches for impact, including in international development and in charitable organisations tackling complex social problems. Our own work has been seeking to identify and learn from different examples and feed them into government efforts, while demonstrating how systems approaches can be used by decisionmakers in sectors such as construction and aviation.

A key goal for government, academics and industry must bring this together into a workable systems approach to net zero policymaking, to make effective decisions and bring the public along with them. One thing is clear: it will be a big change from business as usual and, if we get it right, with faster and more effective decarbonisation should also come better social and economic outcomes.

Keyne Walker is Project Officer at the Royal Academy of Engineering.

The National Engineering Policy Centre’s (NEPC) Net Zero project applies a multi-disciplinary systems perspective to climate change policy. Our work draws on the expertise of diverse engineering disciplines as well as social sciences and systems science.

We explore key issues relating to the transition to a net-zero future, such as infrastructure, governance, skills and resilience, and do ‘deep-dives’ into specific sectors such as construction and aviation to explore the ways they are interconnected and identify transformative routes forward.

Read our work at www.raeng.org.uk/net-zero, or get in touch via nepc@raeng.org.uk.