FST JOURNAL

National Laboratories

DOI: https://www.doi.org/10.53289/FUTG2401

Everything starts with a rock

Dr Karen Hanghøj

Dr Karen Hanghøj is the Director of the British Geological Survey (BGS). She is a geologist with extensive experience in research and innovation management and the minerals and metals industry. Karen is passionate about understanding the complexity of resource management, about environmental and social sustainability, and about the role of geoscience in finding solutions to societal challenges.

Summary:

- The BGS is a world leading Geological Survey organisation and it is focused on public good science and national capability

- The UKRI is a complex landscape to navigate when you are a national lab and it can be challenging to get the right kind of advice to the right people, e.g. to government and policymakers

- What sets the BGS apart as a geological survey organisation compared to other earth science research entities, is the scale of the science delivery. BGS utilises its organisational legacy of knowledge of geology and earth science to address societal challenges at a local, national and global scale, and also work on decadal time scales in monitoring and supplying geological data.

- All of the challenges that we are facing as a society in terms of decarbonisation, and mitigation of climate change hazards and environmental impact starts with understanding the subsurface. BSG can provide maps, models and data for this

- BGS geological mapping and observations feed into widely used products - anyone who uses a satnav (ie. just about anyone with a mobile) uses our data.

- Our products and services are commonly developed with partners, e.g., for natural hazard risk assessment we work together with the Met Office.

We are going to do a deep dive into what the British Geological Survey (BGS) does. Generally, people do not know the British Geological Survey and they struggle with understanding the name and what it means in the context of a research centre. The BGS is a world leading Geological Survey organisation and it is focused on public good science and national capability. It has a national capability in the field of geology and earth sciences, and understanding of the planet. It is a provider of objective and authoritative advice, scientific data, information and knowledge for society. The BGS enables these things to be done at scale. Weinvented the concept of a geological survey organisation, something that almost all countries have today. We are part of the UKRI and the Natural Environment Research Council (NERC) and are one of six centres, two of which are fully owned by NERC. We map into the network of public sector research and government in a convoluted way and the complexity of this landscape, can make it challenging to get the right kind of advice to the right people in, for example, government departments. So I think we need to explore how to best champion this work, and get recognition, and not just in the “great job” sense of the word but how we jointly get the most out of what we know, because it is actually a lot.

Providing Geological data and knowledge for a sustainable future

Our vision is to be a leading and trusted provider of geological data and knowledge to meet societal need for a sustainable future, but what does that mean?

We want to use our knowledge of geology and of earth science to address societal challenges. To do that we generate data information and expertise through observation, analysis and characterization of Earth and its geological processes. Lots of people do this in the earth sciences and what sets us apart is the scale on which we work. Our ability to work at local, regional, national and global scales, and to monitor on multiple timescales ranging from real time to decadal. For example, if you need to know the resources in the UK, you need a national scale project and a national scale organisation to do it. We are also independent and impartial, so we can provide trusted and authoritative information to people. If different stakeholders ask us the same question, they will be getting the same answerand it will be based on what we know about the Earth, and geology. We’ve been a geological survey for almost 200 years, and right now, all of the challenges that we're facing as a society in terms of decarbonisation, mitigation of climate change hazards, and environmental mitigation - all of that starts with understanding the subsurface. I like to say that everything starts with a rock. If you want to understand, for example, improved water security, decarbonisation and net zero, living with geological hazards, such as coastal erosion over the next 20 years, you need to start with understanding the subsurface.

Maps and models

An important priority area for us for the next decade is to produce maps and models for the 21st century. Building on 200 years of legacy knowledge, we want to look at translating that knowledge into products and services that you can use to solve societal problems. We are, updating the Co2 storage database for the UK at a national scale. We are providing data on minerals and supply chains. We are working on geothermal research that can inform policy and regulation. These are just examples and common for these and everything else we do, is that we work closely with different partners across the UK and also in government to deliver them.

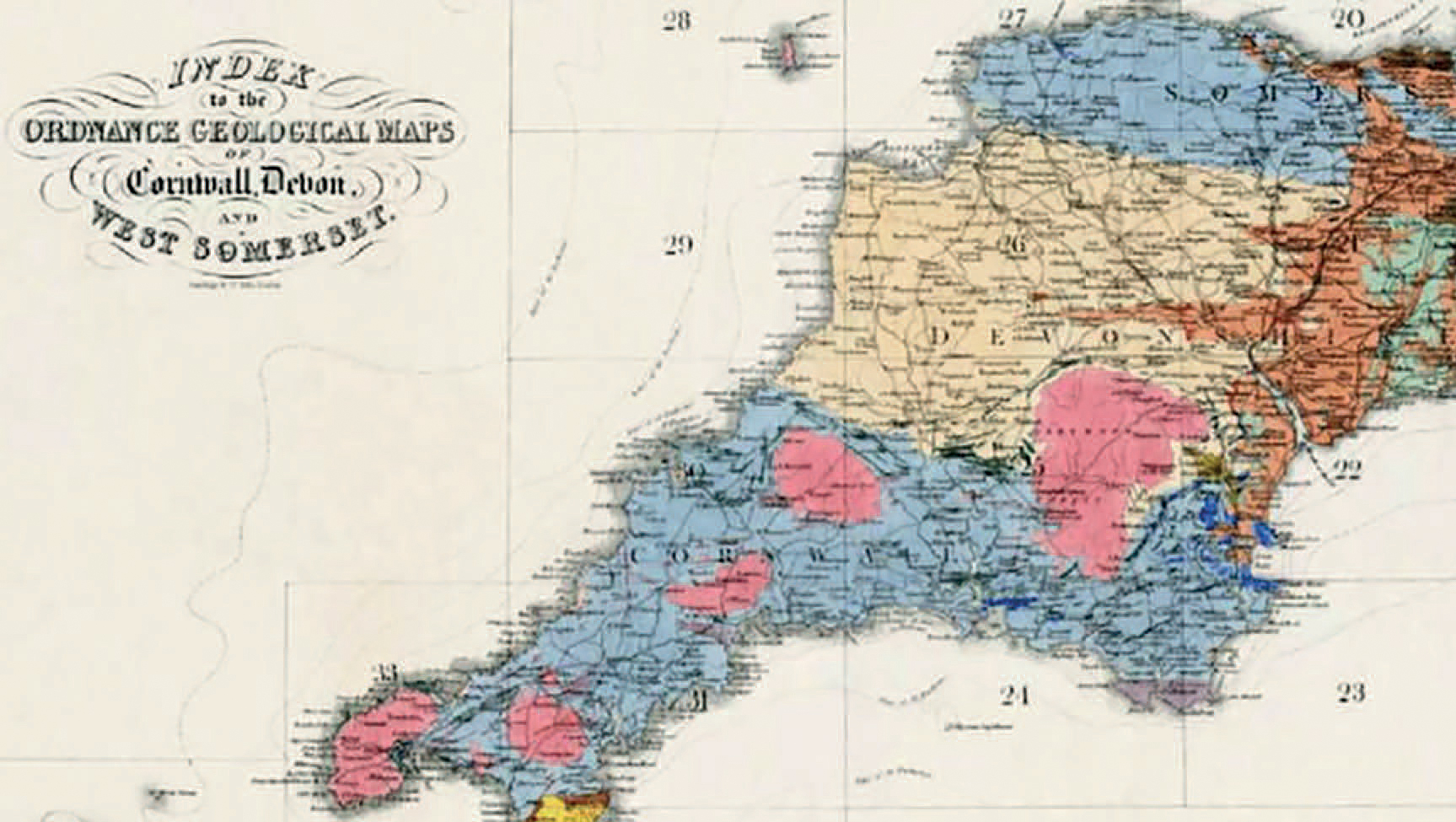

We have had geological maps of the UK for a really long time and these are good maps based on good observations. But with new data, we need new maps. We also think about geology in a quite different way now including understanding plate tectonics which we didn't when many of the maps were produced. Lots of things have changed and maps and models of geology is how the data and the knowledge that BGS is responsible for is being used by society.

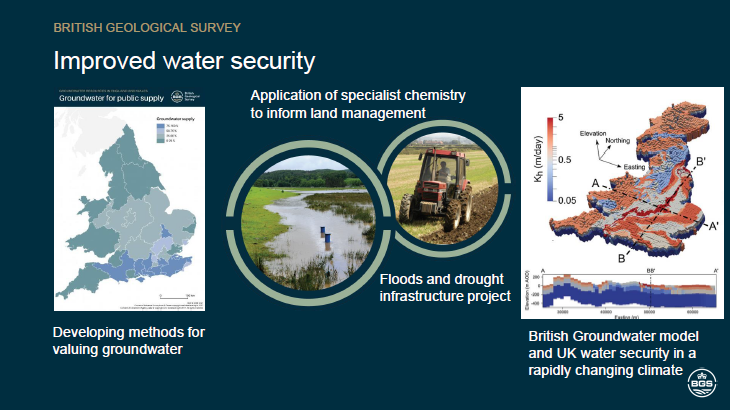

Above you can see a map for developing methods for valuing groundwater and what's deployable. The BGS map produced in 2019 shows groundwater supply as a percentage of deployable output. In the middle there you have flooding at Eddleston and the importance of measuring emergent contaminants in groundwater. This addresses important questions about how we monitor what' is going into our drinking water and how we work with agriculture and the interface between agriculture and geology, and soil science. How do we assess how groundwater flooding is influencing these issues? On the right hand side is a map that shows groundwater levels across Britain simulated by the Environmental Modelling Topic’s British Groundwater Model (BGWM) – in this case based on the August 1976 drought addressing the question of climate change mitigation and how the UK groundwater responds to periods of drought, which is something we will probably be seeing more of.

Our mapping feeds into every day uses too. Every time you look at your satnav, it has data from the BGS in there, because we contribute alongside the Ordnance Survey, Met Office and others to national datasets. We are also working on developing a hazards platform where you can get a one stop shop for understanding hazards such as landslides, flooding and coastal erosion.

In summary - if you need to build infrastructure or you are looking at extracting resources (including groundwater), the first thing that you need is a geological map. Mistakes can be made if you do not know where you are starting from or what you are working with. The urban landscape is a great example. We are used to thinking about the urban environment as a skyline, but think about all the stuff that's happening underground, all of the waste disposal, all of the transportation, the groundwater- this all affects cities. For example, in some large cities pumping up groundwater without the appropriate knowledge is causing subsidence.

What’s next for the BGS?

We are currently looking at upgrading and revising our onshore maps. Also our marine maps. Coastal maps can help provide a lot of solutions to the challenges that we are facing right now regarding raw materials, energy security and decarbonisation. About 20 or 30% of the gravel and sand that we are using for building roads and houses in the UK is being extracted from the marine environment. Not many people know that, but it is true and resource management is going to become increasingly important because there's going to be competitive uses of that space. We also need new habitat mapping which is significant for both resource management and living resources. Spatial Planning of the subsurface, both onshore and offshore, is going to be very important for infrastructure, but also for national security. Maps and knowledge about the subsurface will help address questions of how we create security for our infrastructure in the offshore and in the onshore environment? This scale of work would need to be done with partner organisations over two or three decades. Another big challenge that this country is facing is what are we going to do with our radioactive waste. It’s potentially very controversial, and it is very difficult but it is a real and important environmental challenge and the BGS will need to be involved in helping to solve it. Whatever you put into the ground, you need to understand how the rock is going to behave. We have experiments at BGS that has been running for more than 15 years on the properties of rocks that may be suitable for storing radioactive waste. We can run experiments for decades which shows the kind of timescales that we are able to operate at, at BGS.

The BGS is fairly small in comparison to other national laboratory organisations currently with 641 staff. We produce numerous reports and publications. The Natural Environment Research Council (NERC) Open Research Archive (NORA) had 369,600 downloads of BGS publications last year. That is more than 1000 downloads per day and shows that the expertise that BGS has is in high demand. Our staff are thinking about solving real world problems, they are thinking about geoscience in the context of societal challenges and they are thinking ahead for solutions for tomorrow’s society.