FST JOURNAL

Research Integrity

DOI: https://www.doi.org/10.53289/WMBP7960

The revolution in publishing ethics

Sarah Jenkins

Sarah Jenkins is the Senior Director for Research Integrity & Publishing Ethics for Elsevier. Sarah and her team promote research integrity and publishing ethics through policies, best practices, and education, support Elsevier’s Publishing Teams and Editors to investigate and resolve concerns about the integrity of published papers, and work with specialists across Elsevier to build tools and develop processes that detect unethical practices during the manuscript submission and peer-review process.

Summary:

- Publishing ethics has undergone a revolution in the last five to ten years and article retractions are increasing sharply

- The number of retractions of UK authored papers has remained pretty steady throughout this particular period and absolute numbers are low

- Problems with data, which included both fabrication and falsification as well as honest errors, was the most common reason for articles of UK-authored papers to be retracted

- The UK is in a unique position in that we have been able to keep breaches of Research Integrity and publishing ethics to a minimum

I'm going to explore Research Integrity from a publisher's perspective and share some observations from my role as a publisher and Director for Research Integrity and publishing ethics.

Firstly, publishing ethics has undergone a revolution in the last five to ten years and article retractions are increasing sharply. In 2023, for example, Elsevier (my publishing house) retracted over 850 articles. That's more than double the number of articles that we have ever retracted in a single year, up until that point. This year that number is going to increase further. Article retractions are increasing due to systematic manipulation of the scholarly publishing process, both by individuals and organisations, for gain. Sometimes that gain is financial. For example, when we see authorship positions being sold on papers, sometimes that gain is around increasing impact and output metrics. This leads to professional promotions and invitations to speak at scientific conferences and events. Indeed even invitations from people like myself to sit on the editorial boards of scholarly publishing journals. In turn, that means the publishing ethics cases that come to my door are far more complex than they have ever been. They often encompass multiple papers published in multiple journals, across multiple disciplines. This takes a lot of investigative skill, tooling, and time to resolve. However, if we think about the UK, is it true to say that there is a revolution here on our shores?

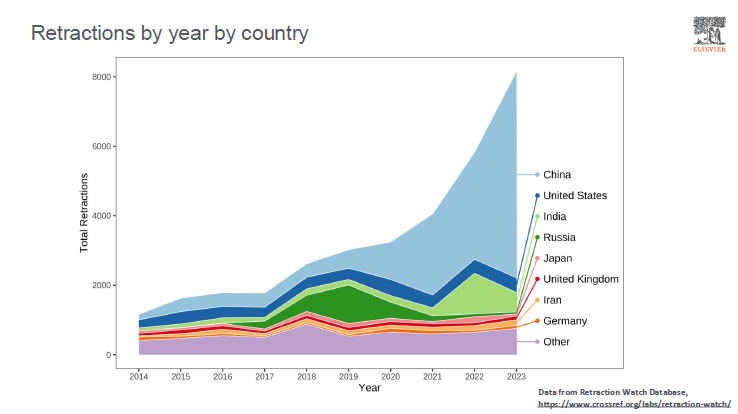

The graph above shows data taken from the Retraction Watch database, which tracks article retractions across all publishing journals. What I’ve done here is to map the total number of article retractions between 2014 and 2023. I have then broken that down by country. The UK is represented here by the red line. Fortunately, the number of retractions of UK authored papers has remained pretty steady throughout this particular period and the absolute numbers are also low. In 2021, retraction watch database recorded 99 retractions of articles by UK authors, 78 in 2022 and 109 in 2023. So over the most recent three year period, 286 articles by UK authors were retracted compared with a total number of 17,214 global retractions over the same period. If my math is correct, the UK contributed to only 1.6% article retractions in the most recent three years. However, absolute numbers only tell a certain part of the story. I want to delve a little bit deeper into the reasons that these UK authored publications were retracted.

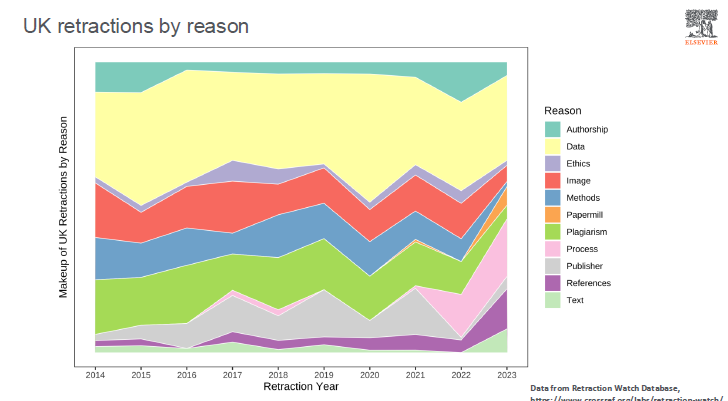

The graph above (using data from Retraction Watch database), shows you the reasons for retraction of UK authored papers between 2014 and 2023. A problem with data was the most common reason. Problems with data can be a very broad reasoning which includes dishonest behaviours such as data manipulation and fabrication. It also serious errors, which mean that the findings of the paper no longer hold up, and also includes not being able to reproduce the data itself. The important thing to note here is that it is often the authors of the work who have discovered these problems post publication, and have done the right thing by coming to the journal editor and requesting retraction so that other authors do not build on invalid results. Retractions aren't always negative. They are a necessary correction of the scientific record.

Process and reference

Am I being hasty in my conclusion that the UK doesn't have the same problems as some of the other countries? There are two other categories that I'd like to point out. The first is “process” and the second is “references”. Process refers to any issues during the course of the editorial evaluation and review process which have compromised the acceptance of that article. References refers to any form of citation manipulation, or indeed papers that cite a rather large number of other retracted articles, meaning that the editor has perhaps lost confidence in the findings. There is a marked uptick for these in the UK, and both categories grew in 2022 and 2023.

I think that a question we need to ask ourselves is: are those two categories going to have grown further in say, five or ten years? Does the UK have the same kinds of problems as other places or does the sharp uptick in 2022 and 2023 simply represent a cleaning up of the scientific literature by publishers? Are we now more alert to some of the problems in our historic published papers and have better techniques to identify them?

So having spoken a little bit about Article retractions, how do we, as publishing houses, uphold both research integrity and publishing ethics? Most publishing houses have specialist teams who work together with editors and publishers to do this. We usually have four main areas of responsibility regardless of which publisher we're talking about.

- We need to detect potential fraud or unethical behaviours in submitted manuscripts prior to publication, to make sure that we protect the scientific record.

- We need to make sure that we resolve concerns in published articles, both efficiently but also transparently so that the community can understand what went wrong.

- We need to ensure that our policies continue to evolve so that they reflect the realities of today and are in step with the expectations of the community.

- We need to collaborate. We must not only share informal data, but also technology and expertise across different publishing houses.

The central message that I think many of us on the panel have tried to impart is that science does a huge amount of good. The UK is in a unique position in that we have been able to keep breaches of Research Integrity and publishing ethics, to a minimum. So perhaps part of the discussion we can have is; What makes the UK so unique, and is there anything that we can impart to some of our colleagues in other countries?