FST JOURNAL

Foundation Future Leaders 2024 Conference

On Friday 8th November 2024, the 2024 cohort of the Foundation for Science and Technology’s Future Leaders gathered in Birmingham to discuss building careers and skills in science and technology for national and global challenges. The conference heard from speakers from academia, industry and policy, at a wide range of career stages and from diverse backgrounds. The day also included break-out sessions where participants came together to consider how academia and industry could work together with government to help achieve the new Labour government’s five core missions. Across the day, several common threads emerged and these are summarised below. View the recording of the conference.

DOI: https://www.doi.org/10.53289/CIVM2963

Building careers and skills in S&T for national and global challenges

Multiple Authors (Foundation Future Leaders 2024)

On Friday 8th November 2024, the 2024 cohort of the Foundation for Science and Technology’s Future Leaders gathered in Birmingham to discuss building careers and skills in science and technology for national and global challenges. The conference heard from speakers from academia, industry and policy, at a wide range of career stages and from diverse backgrounds. The day also included break-out sessions where participants came together to consider how academia and industry could work together with government to help achieve the new Labour government’s five core missions.

Across the day, several common threads emerged and these are summarised below. View the recording of the conference.

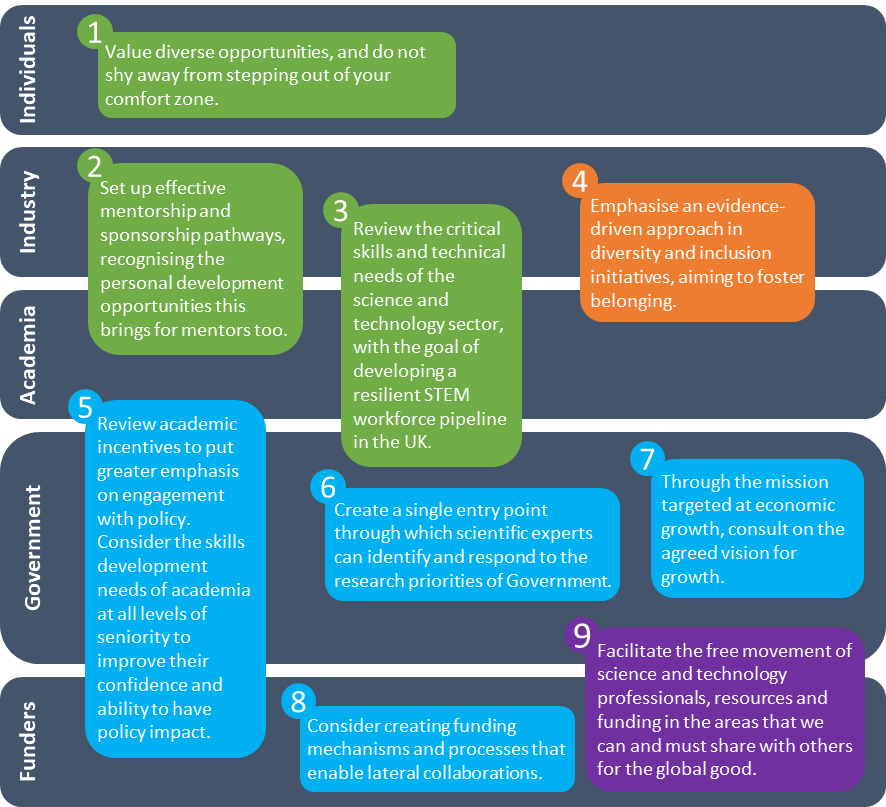

Recommendations The discussions highlighted several recommendations for individuals, industry, academia, government and funders which could help improve the development of talent and skills; equality, diversity and inclusion in science; international collaboration and cross-sector engagement.

- Value diverse opportunities that you are given, and do not shy away from stepping out of your comfort zone to develop new skills and broaden your experiences

- Embed mentorship and sponsorship frameworks in organisations; providing career development for mentors, fostering belonging for mentees, enabling equitable access to networks and opportunities, and ultimately developing the skills of everyone involved

- Review the critical skills and technical needs of the science and technology sector, with the goal of developing a resilient STEM workforce pipeline in the UK. Consider using this review as a platform to improve taught undergraduate curricula, to enhance the environment in which PhDs are completed and develop robust training practices for postgraduate students.

- Emphasise an evidence-driven approach, as opposed to altruism, in diversity and inclusion initiatives. Consider incentives and initiatives that aim beyond inclusion and towards belonging

- Review academic incentives to put greater emphasis on engagement with policy. Consider the skills development needs of academia at all levels of seniority to improve their confidence and ability to have policy impact

- Increase awareness of the structures for integrating policy and science. Create a single-entry point through which scientific experts can identify and respond to the research priorities of Government

- Through the mission targeted at economic growth, consult on the agreed vision for growth. Develop the mechanisms which can realise growth against the agreed vision

- Consider creating funding mechanisms and processes that enable lateral collaborations and exploratory research and innovation

- Facilitate the freer movement of science and technology professionals, resources and funding in the areas that we can and must share with others for the global good. Encourage R&D solutions that have potential for a wider global impact rather than more “western” centric positive outcomes. Consider the synergies between what researchers value in the discovery cycle and the social value of economic growth to clarify what the is purpose of increasing the research wealth of the nation so that the mechanisms better align with a clear motivation.

Leadership and Career Development

Jenny Hindson is a marine climate change policy delivery manager for the Scottish Government. She worked as an Oceanographer for many years, and then worked as a science advisor within central Scottish Government, covering a broad variety of topics to help best inform policy decision making within Scottish Government. She is now back in the Marine Directorate working in marine climate change policy, specifically considering the marine just transition. She is passionate about ensuring evidence is front and centre of policy decision making.

Whilst some people see career paths and the route to leadership as relatively linear, there is great value in following a less traditional path, developing skills and experiences in different sectors or roles, and taking them onto the next career move. These pathways can often involve stepping outside of one’s comfort zone and embracing new challenges, and in doing so gaining a diversity of experience that could otherwise be missed, and can lead to fantastic leadership roles. Sarah Sharples, Chief Scientific Advisor at the Department of Transport, spoke at the conference on her route into this position from an undergraduate student in psychology into a professorship in engineering and into the CSA role, highlighting that a windy route into leadership is possible, and can be very beneficial.

Leadership skills often develop over time, and advancing these skills whilst on your career journey can build confidence, enabling individuals to apply and succeed in roles that go beyond their initial academic or professional training.

Recommendation for individuals: Value diverse opportunities that you are given, and do not shy away from stepping out of your comfort zone to develop new skills and broaden your experiences.

For many of us mentorship can be a hugely valuable aspect of our career journeys, with the power to inspire, influence and guide us on our way. For future generations of scientists, a mentor can provide access to information about job roles and organisations that are otherwise relatively hidden, and provide an informal network for opportunities, as well as advise and support on university or further training. Further along your career path a mentoring relationship can provide further inspiration and advice, supporting career advancement and helping with navigating challenges. For under-represented groups mentoring can be an invaluable source of information, build confidence and lead to finding a supportive network (see also the section on Diversity and Inclusion).

Recommendation for academia, government and industry: Set up effective mentorship pathways, where being a mentor is viewed as a personal development opportunity, to encourage staff to provide mentorship to young people and encouraging a propagation of skills throughout an organisation.

Skills Development and Talent Acquisition

Dr Fabrizio Ortu is an Associate Professor of Chemistry and Sustainable Technology Lead at the University of Leicester. Fabrizio has been involved in academic research for over 15 years, working on a number of projects covering quantum computing, nuclear materials and green chemistry. Fabrizio’s main research passion is sustainable manufacturing, and his research team works on the development of new technologies that could reduce the carbon footprint of chemical processes, and break their reliance on critical materials and precious metals.

The science and technology skills pipeline was a key topic of discussion across all sessions of the Conference. One of the pillars of sustainable technological and economic growth is the identification of skills gaps in key industries, so that strategies can be put in place to support the science and technology sector at its core. The new Mission-led approach of the UK Government heavily relies on the ability of the wider science and technology community to deliver on large infrastructure projects, thus requiring very close collaboration and mobility between sectors. This was a key point of discussion in the Clean Energy Superpower breakout session, where participants discussed at length the delivery targets of the Government’s related Mission. Because of the scale of the challenge to increase our renewable energy production and energy storage capabilities, it is imperative that people coming out of their scientific training are equipped with the necessary technical skills, such as engineering, chemistry, software and programming skills. Academia still plays a pivotal role in providing these tools to the private sector, but it can be slow to respond to industry skills demands. Often, this is the result of teaching practices and curricula being constrained by dated accreditations awarded by governing bodies that are not fully synchronised with critical workforce needs, and do not reflect strategic priorities for economic and industrial growth. Therefore, promoting a symbiotic relationship between academia and industry will go a long way in ensuring academic institutions are providing the skills needed by the workforce (a key message that emerged from the Growth breakout session). In turn, this will align teaching practices and outcomes with ‘real world’ industry demands.

Recommendation for academia, industry and government: Establish a good synergy between private sector and academia, to ensure taught curricula across STEM are modernised to support critical workforce needs of the science and technology sector,

Another key component of the discussion across the sessions was the need to encourage mobility of talent across sectors, particularly between academia, industry and the civil service. Mobility must be considered a resource for science and innovation because of the scientific and societal added values it brings to the table, particularly with regards to widening opportunities for a skilled, resilient and diverse workforce. As discussed in the Breaking down barriers to opportunity breakout session, effective mentoring of future generations of scientists can be a catalyst to breaking down barriers to STEM careers and boost mobility across sectors, also exemplified by some of the success stories discussed during the Conference (see Leadership and Career Development). All these ingredients are essential to enrich the scientific community and equip our workforce with the necessary skills to deliver on Missions set by the UK Government.

Diversity and Inclusion

Dr Lauren Thomas-Seale is a Senior Lecturer in Engineering Design, a chartered engineer and strong advocate for diversity and inclusion. She leads a research group at the University of Birmingham which develops design methods for advanced manufacturing and transdisciplinary engineering, with applications in healthcare. She is passionate about increasing diversity in engineering, and inclusive processes are integral to her teaching and research. Lauren aspires to create innovation and engineering design techniques, which leverage the diversity and agility of thought, which is present in inclusive teams, to ensure that the future of engineering is globally sustainable for everyone.

To ensure that the economic growth generated by the UK science and technology sector is socially inclusive and environmentally sustainable, it is imperative to ensure that the natural diversity of our society, i.e. the diversity of knowledge and thinking within innovation, is reflected through the workforce. As such, diversity and inclusion underpinned all the themes discussed during the conference. Whether explicit or implicit to the presentations and panels, the value of diversity and an inclusive approach was showcased. Further to this, the importance of an evidence-driven-approach was emphasised. It was discussed that (as opposed to being purely altruistic), initiatives need to be driven by data to ensure that outcomes are efficient and effective.

The McKinsey reports (Why Diversity Matter, 2015; Delivering through diversity, 2018; Diversity Wins, 2020) are well cited resources when making the quantitative and financial business case for diversity. It is well acknowledged that a diverse workforce brings different perspectives, creativity and problem-solving capacity, which is inclusive of the society which we endeavour to serve. Diversity drives impactful innovation. Yet almost 10 years after the 2015 McKinsey report was published, attracting, developing and retaining diversity in science and technology is still a widely unresolved challenge. Whilst promoting inclusivity and accessibility is key to attracting diverse talent, inclusion itself is not enough. Where inclusion is about being given a seat at the table, belonging is a feeling which represents qualities such as being valued and welcomed into a community and being given the opportunity to thrive.

Recommendations for academia, government and industry: Emphasise an evidence-driven approach, as opposed to altruism, in diversity and inclusion initiatives. Consider incentives and initiatives that aim beyond inclusion and towards belonging.

The conference reflected on the value of a doctoral degree, the post-graduate research training that some scientists undertake. Whilst the value of a PhD is often promoted through career trajectory and long-term salary, for many doctoral students, the value lies in career skills, and social and personal development.. The often unspoken yet crucial, fact is that PhDs are very hard. Current doctoral training requires high levels of resilience in a person as well as time - PhDs are essentially full-time jobs. They are particularly difficult to do if you are self-funded, have caring responsibilities or are the first in your family to go to university. Whilst it requires resilience to work in science and technology as a member of a marginalised group, additional socioeconomic challenges can make it even harder. Importantly, the term “resilience” itself was questioned, implying needless suffering in the pursuit of an academic career. Many science careers exist outside of academia, but post-graduate research students are not routinely exposed to, or trained for, them.

Recommendations for government and academia: Review the environment in which PhDs are being completed, what professional (as well as technical) skills are being developed, and how this is developing the pipeline and shaping the science and technology workforce.

During the breakout sessions, mentorship was discussed as particularly useful for those from lower socioeconomic backgrounds who might not have existing connections in STEM. or networks. This is where sponsorship is also important. To sponsor means to elevate a person, to connect them to more opportunities and advance their career. The distinction between mentorship and sponsorship is important; sponsorship can be developed from a mentor-mentee relationship, but it requires the active choice to advocate for and advance that person.

Recommendation for academia, government and industry: Set up effective mentorship, sponsorship or equivalent schemes, to foster a sense of belonging for people from marginalised groups. Aiming for equity, by enabling them to access similar professional networks and career opportunities, as the dominant group.

Integration of Science and Policy

Myriam Telford is Head of International Data and Analysis at UK Research and Innovation (UKRI). Myriam has a decade’s experience in research funding, much of which has been focused on working with global partners to enable international R&I collaboration. She is passionate about using data and evidence to understand the role of collaboration in modern research and innovation endeavours, reduce barriers to collaboration, and evidence the value of being globally engaged to address global challenges.

Research can play a critical role in shaping policy-making. Where strong relationships exist between the scientific community and policy-makers, this can ensure that policy decisions are informed by the latest scientific knowledge and, conversely, increase the impact of research by ensuring its rapid translation into practical application in policy.

For this reason, there are multiple formal structures in place across government to enable the integration of science and policy. Sarah Sharples, Chief Scientific Advisor at the Department for Transport, spoke at the conference on her role in facilitating relationships between her policy colleagues and scientific experts across a range of fields. As well as convening experts – both ongoing through the Science Advisory Councils and ad hoc for specific projects, Chief Scientific Advisors play a role in translating between the two communities. Similar convening structures exist across other aspects of the UK’s policy-making, for example the Parliamentary Office of Science and Technology sources impartial scientific research for parliamentarians.

Whilst these structures are an important step, they can often be complex for an external audience to navigate, especially when government research priorities are rapidly changing. The creation of Government Missions is encouraging new ways of working across departments: this has advantages in breaking down silos and pinpointing the key priorities of Government but also may make it more challenging for the scientific community to identify the best entry route for sharing their expertise.

Recommendation for government: Increase awareness of the structures for integrating policy and science. Create a single-entry point through which scientific experts can identify and respond to the research priorities of Government.

A further challenge in the integration of science and policy is the nature of Government work: often driven by a need to solve a specific task in a challenging timeframe. This reduces the time available to engage with external advice, increases the imperative for a simple, consensus-driven answer, and aligns poorly with academic funding, project and publication timelines. Some Government departments are setting up a ‘Futures team’ with a remit to explore long-term trends and engage with emerging thinking beyond an immediate policy need.

However, addressing this barrier also requires a cultural shift within academia. Further work is needed to ensure that academic incentives – including the Research Excellence Framework (REF) assessment, as well as career progression within institutions – recognise alternative routes to value creation from research beyond traditional outputs such as publication. Engaging with government also requires a new skillset: it may require researchers to look beyond their own area of specialism to represent cutting-edge knowledge from across their field, and it calls for the ability to communicate complex and nuanced information to a lay audience in a succinct way. And, sometimes, it requires a re-thinking of what is impactful: in the words of Sarah Sharples, “Sometimes we want science to be reassuringly boring.”

Recommendation for academic institutions and funders: Review academic incentives to put greater emphasis on engagement with policy. Consider the skills development needs of academia at all levels of seniority to improve their confidence and ability to have policy impact.

In a world of rapid scientific and technological progress, policy-makers need access to cutting-edge research to support their decision-making. But, overcoming the natural silos between the scientific and policy-making communities requires cultural shifts on both sides.

Economic growth and value of R&I

Dr Christopher Pilgrim is in the Materials and Manufacturing team at Innovate UK Business Connect focussing on facilitating innovation towards resource and energy efficiency. Chris supports the Transforming Foundation Industries Challenge and other projects including AI applications in the materials value chain.

His background is in materials and mechanical engineering. He completed an engineering doctorate with an Imperial College spin-out company looking into smart coating materials and measurement. Since, he worked in technical management roles to drive the development of the technology for commercial applications and then in quality assurance for a global aerospace manufacturer.

Economic growth is traditionally measured by Gross Domestic Product (GDP), but this narrow focus misses the broader factors that truly define a nation's well-being. True, sustainable growth involves not only financial metrics but also elements like health, education, and societal happiness. It also requires considering the consumption of resources and the long-term environmental impact. While research and innovation (R&I) can drive progress on these fronts, their benefits are often long-term, requiring patient investment. In times of financial strain, investment in R&I is often cut which can stifle economic recovery by limiting the pathways to future growth.

The contribution of science and technology to the economy is important but difficult to quantify and often under-estimated. In the breakout session on economic growth, much of the discussion related to the balance between funding R&I with clear return on investment versus allowing more emergent benefits. Taking a simple return on investment approach, fails to account for the less tangible, but highly impactful, contributions of scientific and technological advancements.

Take, for example, the development of the Covid-19 vaccine. Beyond its direct health benefits, the vaccine helped restore productivity, enabling economies to reopen and recover. Similarly, innovations like fibre-optic cables, which were developed through basic research in the 1960s and 70s, now form the backbone of global internet infrastructure. Despite their low-cost production, their impact on global connectivity—and, by extension, economic growth—is immense. This illustrates the need for a broader definition of economic value that includes long-term societal and technological benefits, rather than just immediate financial returns.

The rapid commoditization of new technologies further complicates the economic impact of R&I. As technologies mature, their potential for driving economic growth diminishes unless supported by strong manufacturing capabilities and robust supply chains. This means the true value of R&I often lies not in the immediate commercial payoff but in the foundational changes it makes possible over time.

The UK has made some of the most significant scientific and technological breakthroughs in history, yet the full economic impact of these innovations has often been distributed across multiple countries over many decades. As we enter an era marked by increasing international tensions and climate-related risks, international collaboration will be critical in translating world-leading research into tangible economic benefits for the UK. Opportunities for such collaboration were discussed in the final session of the conference.

Collaboration between academia and industry is also essential for the translation of research to innovation. Programmes like Knowledge Transfer Partnerships (KTPs) and industry-sponsored PhDs bridge the gap between academic research and real-world business needs, fostering a symbiotic relationship that benefits both sectors. Tax incentives, knowledge sharing and other methods to encourage researchers to commercialise innovation will help drive economic opportunities.

As mentioned in the closing session of the conference, there is a clear ambition for economic growth in the UK but no collectively agreed purpose for this growth. As such, we have the mechanism but without the motivation. Falling between the US and EU, we need to have a clearer picture for the reason for growth which will in turn help define a more effective path forward.

Recommendations for government: Through the mission targeted at economic growth, consult on the agreed vision for growth. Develop the mechanisms which can realise growth against the agreed vision.

Similarly for industry, purpose-led businesses are more successful than the competition. Establishing and articulating a clear purpose will help drive growth, retain talent and increase impact.

Innovation and Emerging Technologies

Sam Islam is a Systems Engineering Consultant based at Energy Systems Catapult. Her key role is performing research and development activities and leading and providing technical expertise in the UK's journey to Net Zero for projects ranging from zero emissions shipping to sustainable cooling. She has over a decades worth of experience working in Renewables, International Development, Offshore Oil and Gas and Transport industries. Sam has worked on international assignments across Europe, Asia and the Middle East and Africa across both public and private sector organisations and businesses. She is a member of INCOSE UK and the IET and is passionate about inclusive innovation and ensuring the equitable development of solutions to address the climate crisis.

The UK has a storied history of innovation within science, medicine and engineering ranging from Fleming’s accidental discovery of Penicillin to the development of the steam engine, which propagated the industrial revolution in the 1800s. As highlighted in the breakout panel for “An NHS Fit for the Future”, the COVID19 epidemic is a very recent example of how unexpected global challenges demonstrate the more disruptive pathway to innovating through the development of the COVID19 vaccine. Beyond the technological breakthroughs that have followed and will follow because of this achievement, the pandemic has also elicited some complex lessons learnt regarding public health and emergency preparedness, which are finding application in other areas such as wastewater epidemiology. The pandemic has also helped to identify the broader healthcare challenges such as the need for data that more accurately reflects the diversity of the current population to further opportunities growing within the personalised medicine space.

This echoes a key point noted within the “Clean Energy Superpower” breakout panel where the topic of library and information sciences was discussed and the potential role that this field could play in enabling improvements in the standardization of taxonomies and ontologies across science and technology activities regardless of discipline. The specific role of digital archiving was also discussed to understand the importance of consolidating historical data with more recent data to aid ease of collective data retrieval and facilitate more innovation mining activities through minimising the risk of “reinventing the wheel.”

In both breakout panels, it was noted that although there is collective understanding and recognition of the importance of being discipline agnostic in addressing the key challenges outlined in the current government’s mission led strategy, in practice, current funding mechanisms for interdisciplinary, multidisciplinary, transdisciplinary and cross-disciplinary approaches differ considerably. This constrains opportunities to explore more uniquely lateral collaborations that could yield the scale of innovative breakthrough that is typically reserved for more unprecedented times.

Lack of appropriate funding can also create a barrier to supporting new technologies being integrated wholly into existing systems; this was discussed in the NHS Fit for Future breakout panel, where the initial cost of introducing new and more effective treatments needs to be balanced with the benefits of existing treatments that have already been proven in service. It was also noted in the Clean Energy Superpower breakout panel that a key area for innovating within the clean energy space is addressing the challenges of scaling up existing solutions such as waste storage to accommodate the increasing up take of small modular nuclear reactors in the UK.

Recommendation for funders: Consider creating funding mechanisms and processes that enable lateral collaborations and exploratory research and innovation.

Although mission driven collaboration has so far enabled the identification of such challenges, openness to supporting exploratory, “curiosity driven” collaboration activities that don’t have a deliverable defined from the outset could lead to the identification of brand-new research areas that wouldn’t ordinarily be elicited from existing research methodologies. This would require a different approach to funding and preliminary work to understand which subject matter areas are currently underutilised within the given research space. This is reflective of a comment made in one of the breakout panels that topics such as the NHS and Clean Energy have a clear relationship with science and technology, however in missions such as Crime and Justice, the role of science and technology beyond obvious fields such as forensic medicine and therefore the value and impact of innovating in these missions is less well defined.

Such open-ended collaboration needs to be paired with the presence of a diverse workforce and this must be achieved through proactive measures to improve access and inclusivity within training opportunities.

International Collaboration

Dr Geoffrey Neale is a trailblazing researcher in the field of composite materials, focusing on making these materials structures stronger and smarter. Geoff is a Royal Academy of Engineering Research Fellow and Lecturer at Cranfield University whose work has pushed the boundaries of manufacturing multifunctional and innovative composite structures. Always on the cutting edge, he is passionate about making the world more inclusive, safer, and sustainable, by tying in his research to real-world applications.

Today’s global socioeconomic climate is one in which international collaboration is ubiquitous and necessary to achieve efficient, sustainable, and impactful outcomes in the science and technology landscape. The UK is already considered a global leader in research, being at the cutting edge of most fields, but has national ambitions to take this to the next step and become a science superpower. We have been quick to recognize that open collaboration underpins our ability to achieve this superpower status and aim to leverage our position of strength to expand our global impact. However, we live in a volatile world where many challenges are no longer confined to national borders and historical partnerships cannot always be relied upon. Simply put, addressing the barriers to widening international participation in our technological goals and those of our global community is of key importance.

Emphasizing the importance of international collaboration in research is seen as the first step. In the current spending review, UKRI will spend somewhere in the region of £4 billion on international collaborations according to Professor Christopher Smith, UKRI International Champion and Executive Chair of AHRC. He noted that UKRI partnerships are highly concentrated in Europe but spread fairly well globally, with a noticeable underrepresentation of collaborative activities on the African continent, which is being addressed through exciting new initiatives. Many universities are focusing on internationalisation, not just of their research agenda, but by physically installing overseas campuses in emerging markets across the globe. Professor Marika Taylor, Pro Vice Chancellor and Head of College of Engineering and Physical Sciences at the University of Birmingham explains that the benefit here is twofold. Not only is it more cost-effective for these students and researchers to study or work in their own countries, but the physical presence of UK institutions facilitates a more direct link to local governments and industry. This fosters a strong international research and innovation ecosystem, driving up research quality and providing two-way access to the full research and innovation pipeline in both countries.

Open research policies like FAIR (Findability, Accessibility, Interoperability, and Reuse) principles underpin scientific rigour and allow for greater dissemination of research outcomes that allow the global community to adopt and build on our outcomes to the benefit of us all. This maximises the return on research expenditure and creates new opportunities for researchers in the UK to engage with a wider pool. Mr Alex Hale, Technology Programme Manager at the National Composites Centre explains that our R&D challenges are often tied to global challenges where the faster spread of new and emerging technologies can sometimes be plagued by barriers like knowledge access and freedom to collaborate. Export control regulations, although necessary and well-intentioned, can sometimes prove a hinderance to broadening our partnerships. Sometimes the innovations in these areas are extremely complex and judgements on whether export control regulations should apply is incredibly subtle, making it a challenge for these typically small teams that make these assessments.

There are inherent efficiencies gained from internationalisation of research efforts, where shared expenditure and resources helps to reduce duplication of efforts and spending. This is especially poignant in large scale projects where it may be difficult for one country or institution to dedicate sufficient resources. Crucially this also underpins integrity, reproducibility and public trust.

In a globally competitive market, talent acquisition is a continued challenge. We see that there are large skills gaps in the areas vital to our national interests like manufacturing, defence, and pharmaceutical industries. If we are to attract the right talent to support UK ambitions, we must look outward to bolster our workforce and further develop sovereign capabilities. By doing so, the risks associated with relying on limited reliable supply chains, that may in future become unreliable, can be more effectively mitigated.

Recommendations for government: Facilitate the freer movement of science and technology professionals, resources and funding in the areas that we can and must share with others for the global good. Encourage R&D solutions that have potential for a wider global impact rather than more “western” centric positive outcomes. Consider the synergies between what researchers value in the discovery cycle and the social value of economic growth to clarify what the is purpose of increasing the research wealth of the nation so that the mechanisms better align with a clear motivation.