FST JOURNAL

Tackling Racism

DOI: https://www.doi.org/10.53289/YWYN6400

Identifying and addressing the barriers to participation

Ale Palermo

Dr Alejandra Palermo FRSC is Head of Global Inclusion at the Royal Society of Chemistry. Her academic journey began as a chemical engineer, with a PhD in materials science. She became an Assistant Professor in Argentina, before joining Cambridge University under a Royal Society Visiting Fellowship. At RSC, she leads a team working on priority areas such as equity, diversity and inclusion in the chemical sciences, and international large programmes developing inclusive global collaborations.

There is ample evidence that Black and minority ethnic students face a number of barriers in Higher Education in the UK, from simply access, to representation, to curriculum content (some refer to a ‘colonisation curriculum’), to the delivery of that content – all aspects of the overall experience that they have at university.

White students are 13% more likely to get a first or upper-second class degree than Black and ethnic-minority students. This disparity continues – indeed increases – on the journey to postgraduate attainment and academic careers. That results in a pay gap and fewer opportunities for research funding or promotion. It also impacts the outcome of their research and its visibility.

Overall, there is an under-representation of UK students from ethnic minority backgrounds in postdoctoral programmes. This has been recognised recently by the Office for Students and Research England, which have provided £8 million to fund 13 projects aimed at tackling inequalities in access to postgraduate research. One crucial issue that has emerged is the under-representation of Black scientists in Higher Education research centres. This is more acute in some disciplines than others.

A case study

Chemistry can serve as a case study in understanding some of the issues behind these inequalities. The Missing Elements report1 paints a stark picture of the realities experienced by Black and ethnic-minority students. The report is based on data and evidence gathered over two years of research. It brings together the available data, including Chemistry-specific data from the Higher Education Statistics Agency (HESA), data drawn from our membership as well as our boards, committees and so forth. We also consulted the community. Through this, we tried to understand the lived experience of Black and ethnic minority scientists.

We spoke to hundreds of people about what happens in different career stages as well as those who influence chemistry, like funders and policymakers. The study reached beyond academia to industry but also included teachers and it had an international dimension as well. Given the hard data and evidence, there really is no excuse to avoid tackling the issues and addressing the observed inequalities. That of course includes the Royal Society of Chemistry.

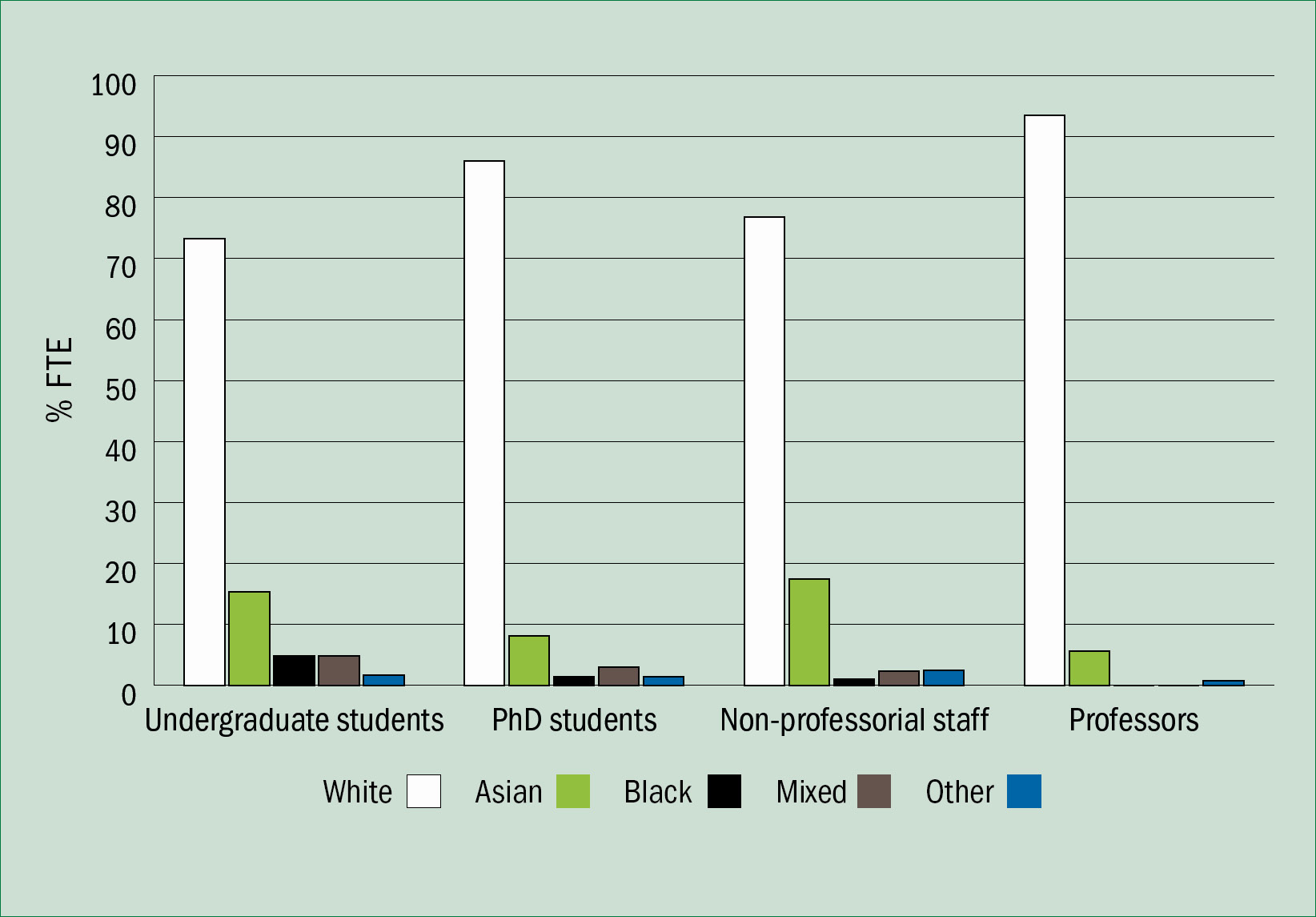

Figure 1. The UK is losing Black chemists at an alarming rate.

Figure 1. The UK is losing Black chemists at an alarming rate. By analysing HESA data for 2019-20, the ethnicity breakdown of students and staff in chemistry can provide an indication of the progression of Black and minority ethnic individuals within the chemistry pipeline (Figure 1). The data show a clear retention problem, which is particularly pronounced for Black chemists. The economy is losing these professionals at an alarming rate. Black undergraduate chemistry students account for 4.9% of the total, which is higher than the 3% of the general UK population who are Black, but it is still low. Yet, the figure then drops significantly to 1.4% for PhDs, 1% for non-professorial and finally zero for chemistry professors. We know there is at least one Black professor in chemistry, possibly two, but in percentage terms this is reported as zero.

A similar trend is visible with RSC membership. Looking at seniority across the different membership categories, there is a drastic drop in terms of Black representation. It is important to note that membership includes chemists working in many different disciplines as well as industry, policymaking, teaching, etc – and of course the RSC is international so it complements and reinforces the conclusions from the HESA data.

Looking at the attrition which is observed at later career stages, we looked into where the undergraduate students are going. It appears there is a smaller proportion of Black undergraduates at Russell Group institutions. Of all chemistry students, 55% attend Russell group universities, but only 37% of these are Black. This indicates a structural challenge as Russell Group institutions are more research-intensive and have more funding. So, the opportunities that students have by going to Russell institutions, in terms of progressing to PhD and so forth is likely to be greater. Consequently, the under-representation of Black and ethnic minority students at Russell Group institutions is very important.

We also looked at the intersection between race and ethnicity and gender. It is not surprising that there is a loss of female chemists independent of their race or ethnicity. Yet the loss of Black women is much more pronounced than from any other ethnic group. Of Black undergraduate students, 60% are women. But once again, the numbers decrease dramatically with seniority.

Lived experience

We investigated the lived experience of hundreds of people from minority ethnic backgrounds working in chemistry globally. This qualitative research indicated that there are a number of interconnecting factors that

impact their success in chemistry, from structural, funding and cultural issues to the availability of mentoring, leadership roles and role models. These are very similar to those faced by women more generally. However, for Black and ethnic minority chemists, the persistence of the issues is much larger. There is, after all, the longstanding historical context of racial discrimination that adds a further complexity to the topic.

1 RSC Missing Elements report www.rsc.org/new-perspectives/talent/racial-and-ethnic-inequalities-in-the-chemical-sciences